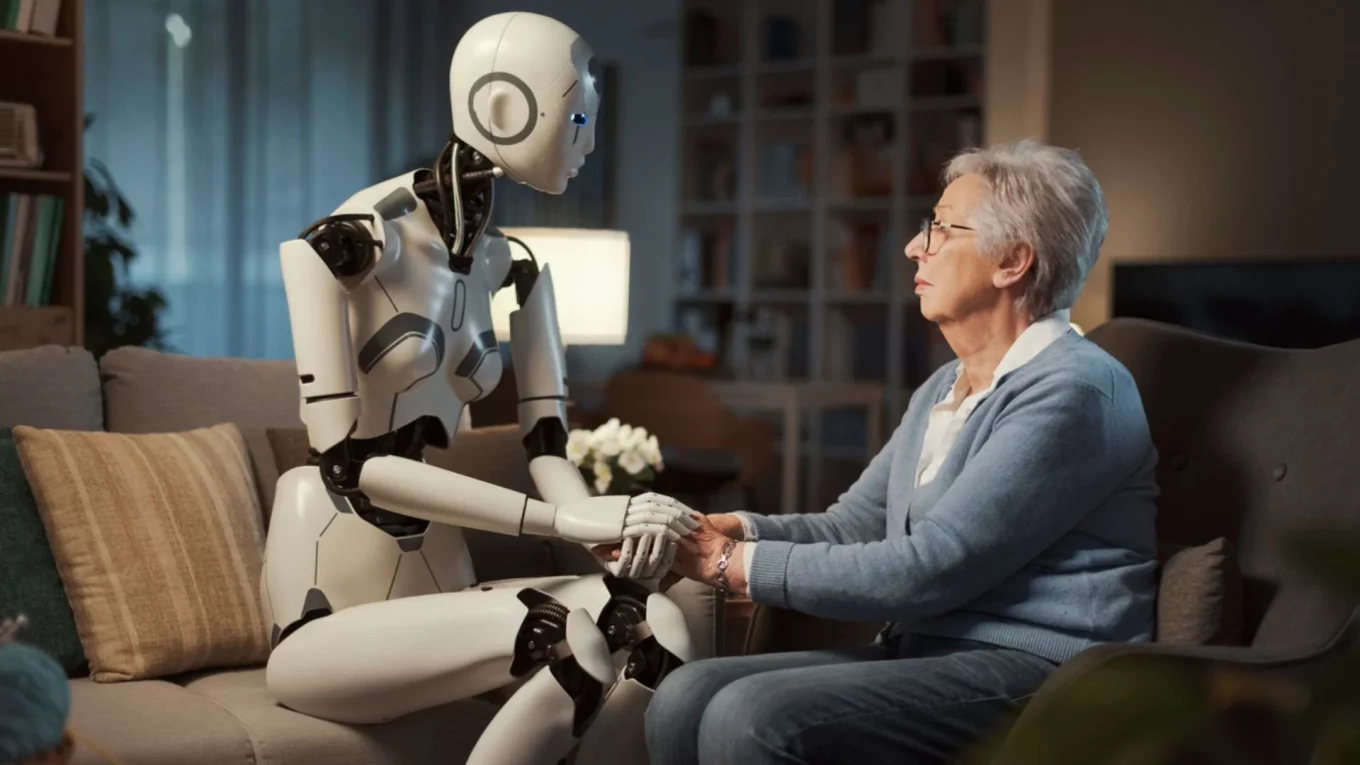

Would you turn to a robot for psychological help?

AI-based mental health tools are gaining more followers and are already useful in certain tasks and situations.

AI has numerous applications in the practice of psychology.

By now, it’s almost hard to believe that less than two years ago, most of what we now consider routine was still science fiction. Today, we casually talk about generative AI and its many applications in creating almost any type of content. ChatGPT, for example, surpassed 180.5 million active users in December 2023, and was named the app of the year by Android users. The presence of AI in our daily lives is nearly ubiquitous, extending to fields such as entertainment (streaming platforms), scientific research, education, marketing, and healthcare. And of course, this also includes psychology.

But would you turn to a virtual therapist powered by AI for psychological help? “Probably, depending on the problem,” admits Rubén Nieto, a professor at the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC). “For some people, it may be easier to engage through a machine than with a person (…). Plus, the cost is likely much lower, and it could be an entry point for psychological care, which we are currently not providing enough for,” he suggests.

Indeed, one of the most popular conversational bots on Character AI, the app of the year according to Google, is called Psychologist. According to the BBC, it received 18 million visits just in November 2023. The platform also includes 475 robots with names like “therapy,” “therapist,” “psychiatrist,” or “psychologist.”

A notable example of AI’s role in psychology is an experiment in the US in the early 2000s, where an avatar of a psychologist was created in a virtual world to treat post-traumatic stress disorder in war veterans. “The avatar was very well programmed, showing empathy, making patients feel understood, asking about their problems, and making them feel comfortable,” explains Nieto. “Some veterans found it easier to talk to that avatar than to a real person.” Interestingly, this wasn’t even a pioneering system: one of the first conversational bots, Eliza, was created in 1966 by Professor Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT, based on Carl Rogers’ psychotherapy method.

What applications does AI have in psychology?

Considering the use of AI applications in psychology raises some concerns about their suitability and effectiveness. For example, one might wonder if we risk becoming reliant on a virtual therapist and avoid seeking a real professional when needed. Or, given that AI is only as good as the data it’s trained on, we might question who programmed it and whether they are experts in mental health.

“The risk is that if you search on Google for ‘AI psychological interventions,’ you might encounter a machine whose programmer and data sources you don’t know. But if it’s correctly programmed and tested, I don’t see it being a problem,” says Nieto. It all depends on the direction the trend takes: “A few years ago, nobody used Google Maps, and today it’s indispensable. I feel that we will end up integrating AI much more into our daily lives, including psychological intervention,” he adds.

For Mireia Cabero, a professor at UOC, AI is already proving efficient in specific tasks, such as the initial screening of cases, diagnosing, and assessing mental disorders, helping professionals with diagnosis and decision-making. AI is also useful in supporting patients through emotional pain processes (such as grief or trauma recovery), self-awareness, and rethinking strategies in less severe life conflicts; to “reduce feelings of loneliness with therapeutic conversations for educational and transformative purposes” and even assess the need for referrals to emergency support units like suicide prevention or severe youth disorders.

Risks and challenges

However, these interventions also pose risks that cannot be overlooked, “such as missing critical, severe cases and potential risks (suicides, eating disorders, substance abuse, among others) due to errors from biases or imperfect algorithms,” warns Cabero. One unresolved question is whether AI might replace the role of a real therapist. For now, this seems unlikely: “AI doesn’t seem capable of replicating human empathy, psychological presence (being and knowing how to be there for others), and the emotional support we humans provide with sensitivity, joy, and our unique DNA.”

When it comes to making proper use of AI in mental health, the strategy, according to Nieto, is to educate the public to discern whether a given technology is appropriate: “This has already happened in health and psychology before. If you had a health issue before AI, what did you do? You went to Google and searched for ‘it hurts here,’ and you got millions of results, many of which were incorrect (…). We need to teach people to check, for example, who created that technology, who and what objectives they developed it for, and so on.”

Community medicine, research, and support

As experts from UOC remind us, the current applications of AI in psychology go beyond those already mentioned. In community mental health intervention programs, for example, AI helps offer personalized content based on standard internet materials, providing exactly what each person needs through interaction.

In research, AI can speed up the search for scientific literature, ensuring professionals are always up to date on the most effective treatments. It can also assist with patient follow-up between therapy sessions.

The shortage of psychologists, a key factor

While the pandemic highlighted the importance of addressing mental health issues, the post-pandemic period has shown that little has changed: “During the high-stress situation, it became very clear that we needed psychologists in the healthcare system. But the situation has gone back to square one,” Nieto laments. The reality, he points out, is that access to the public health system is complicated and clearly insufficient.

“I don’t think we’ve made progress in that regard, and we need to keep working on it politically,” the expert continues. “Not only in mental health but also in other fields where we have an important role, such as oncology, chronic pain, diabetes, and other traditional health issues.”

The shortage of professionals is even more evident when comparing Spain to other EU countries. Spain has just six clinical psychologists per 100,000 inhabitants (three times fewer than the European average), and 11 psychiatrists per 100,000 people, nearly five times fewer than Switzerland (52) and about half the number found in France (23), Germany (27), or the Netherlands (24). Meanwhile, suicide rates and mental health issues continue to rise.